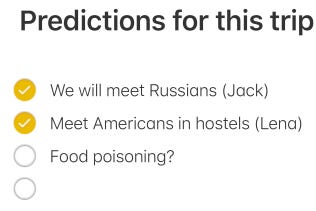

On our first day in Bangkok, Lena and I wrote down our predictions for the trip:

Fourteen days later, two and a half had come true.

The rest of my blog posts click together in my brain— they’re about Kazakhstan, they’re about Central Asia, they’re about travel, and all the other random thoughts from my time abroad. This one feels different because Southeast Asia was different. It doesn’t “click” into place in my brain, and I’ve been thinking about why that is.

So far this year, I’ve been mostly in Central Asia with brief stints in Europe and the Caucasus. I have met new people, eaten new foods, heard new music, touched ancient buildings, witnessed ultra-modern man-made monstrosities, and basked as close to the sublime as I’ve ever come in the natural world. Yet, I had been unconsciously moving myself on a spectrum: a very traditional, linear spectrum, from The West to The Post-Soviet Sphere. It hasn’t been scientific— just feelings and vibes. Skyscrapers in Frankfurt on one end. Khrushchevkas in Almaty on the other. Certain experiences challenged the spectrum, like the sandy streets of Uzbekistan, but for the most part, I unconsciously held onto this linear conception as I traveled.

In our two weeks in Southeast Asia, the spectrum was destroyed, the paradigm dismantled, the existing framework that had helped compartmentalize this year broken. Like lines of children’s chalk after a thunderstorm, it is no more.

Traveling to Southeast Asia was humbling— not because I was overwhelmed by any one thing but because I saw traces of Soviet influence, the repercussions of Western imperialism, and a whole lot else I had never seen before all mixed together. It feels impossible to categorize. As anyone who has been lucky enough to spend time in the region knows, lumping Thailand, Laos, Vietnam (the places we went) and Cambodia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Indonesia, Myanmar, Brunei, East Timor (the places we did not go) under one umbrella term, “Southeast Asia,” feels reductive and borderline insane given those countries’ vast variety of customs, religions, histories, languages, etc.

With that aside aside, here is my fundamentally incomplete SE Asia trip.

Thailand

Upon arriving in Bangkok, we did nothing but wander and sweat. It was heat like that of Nana’s house in south Florida but in a concrete metropolis. It was heat that demanded stopping at every café, bubble tea shop, and fresh fruit stand. I gladly obliged.

The first night we started off toward a pad thai place before being pulled into a pop-up street market. Pad thai, grilled vegetables, fresh fish, Thai roti, pomegranate juice, succulent mango…. Everyone says the food is good— famously good. It delivered.

Bangkok felt like the much-needed vacation I wanted after the end of second semester. In many ways, it felt like the city had been designed to be outward-facing in a way that I had grown unaccustomed to in Almaty.

Once this year, a co-worker said, Almaty is almost a global city, a city where you can find everything and do anything. I think there’s still a fair bit of debate that could be had about how close Almaty is to being a global city, but one thing is for sure: Almaty is not designed to be a global city. It is not set up to appease large crowds of foreigners for either tourism or business.

Bangkok, on the other hand, seems to have been born of two minds: it is navigable and safe enough to attract foreigners without feeling like it was created for foreigners.

So, it felt important to me to be a good steward of that balance, especially when others have not been. Thai people seem remarkably quiet— at least compared to Americans. While riding the SkyTrain, it is almost silent, except when a group of tourists jumps on. The foreigner-local divide was something everyone seemed to be aware of, and though every Thai person I met treated me with kindness and respect, I could also feel the currents of residual tension left behind from ill-behaving foreigners.

Indeed, Bangkok was the first time I had heard “backpacker” used derogatorily.

The Foreigner Report (written by a foreigner): Thailand Edition

On our first day in Bangkok, when I would hear someone speak English, I would turn to Lena and say “aye English,” as we do in Almaty. But soon, I felt like I was pointing out English speakers twice a block, so I stopped. There were two types: the tourists and the non-local locals.

Tourists wear athleisure in Bangkok— both men and women clad in the latest breathable, lightweight, workout-ready but everyday, synthetic material. Tourists look at maps on their phones. Tourists start one way then realize the Google map arrow was miscalibrated, turn on a heel, and run right into someone. Tourists walk around with big cameras. Tourists look up the baht-dollar conversion rate fifteen times a day. Tourists ask to take photos of the fruit vendors and pose under neon signs. Tourists proclaim that this spot in Chinatown is very instagramable.

The non-local locals wear light cotton shirts and loose pants— because “that’s how the locals dress.” The non-local locals have earbuds in. They know that you can never bring durian on public transport. They know not to talk loudly on the SkyTrain because they’re just on their way home to their apartment or to work at the consulting company that’s connecting Western firms to emerging Asian markets and it’s not a big deal. Non-local locals never go to the “backpacker street.” Non-local locals only talk about their local friends even if their best friend is from Germany. Non-local locals know a spot that’s good. Non-local locals hate backpackers but might have an Osprey in their closet.

Laos

Everyone I’ve talked to about traveling to Laos has said that part of their heart will always be attached to the country. I imagine they each have their own reasons for why this country squeezed between Vietnam and Thailand captivated them. For me, it is some combination of these memories that stand out more vividly than anything else on the trip.

Memories of the people:

At 9 am, we played pétanque and drank BeerLao over ice with Bountanh, Onkeo, and Bounkhain, three friends of my Uncle Peter, who showed us around their hometown with care and intellect. The night before, I was talking politics with Billy, my Uncle Peter’s original connection to the country, while watching the sun set over sloping jungle mountains.

On a boat cruise on the Mekong, I heard Russian. I scooched toward a couple quietly talking in the corner of the upper deck and eventually got the courage to ask them in Russian where they were from. We chatted a bit. The guy was from Moscow. The girl was from a border city with Kazakhstan and was ethnically Kazakh, though she had never been to Kazakhstan. They had been working remotely and traveling through Southeast Asia with their cat for eight months. I didn’t have to ask why they had left eight months before given the man’s age, and they didn’t explain.

Prediction #1 - AchievedThank you to the PiA fellows living in Vientiane who graciously let us crash in their house for three nights. To see how three other fellows (and one honorary PiA fellow/Fulbright ETA) made community, integrated into a different city, and lived life abroad was lovely to experience for four days and a bit trippy to reflect upon. To think that we are in the same program, in the same fellowship class, and can shorten our experiences to people back home to simply “we spent a year in Asia” is mind-boggling. Despite that paradox, I’m so grateful that we got the chance to meet them and see a window into their life.

Memories of the tastes:

The tender meat of Mekong River fish.

The charred edges of duck and the bitter flavor of the leafy green which had a name I had never heard of and have since forgotten.

BeerLao, the cheap yet always refreshing light beer that seems to have sponsored the entire country.

Random other memories:

My fingertips burning as I hold out hot sticky rice for the procession of monks walking for morning alms.

The nose-scrunching smell of fresh durian being cut on the streets.

The rough and hairy trunk of an elephant.

The Kuang Si Falls, which apparently didn’t look as impressive as usual due to low water levels. It’s hard to imagine this place could look more picturesque.

Staring at a tiny portion (hundreds) of the inconceivable number of bombs (2.5 million tons, a planeload every eight minutes, 24 hours a day, seven days a week for nine years) dropped by US forces. Laos is the most heavily-bombed country per capita in the world, and yet how many of us could find it on a map?

The bombing of Laos is sometimes called the US’s secret war. It’s not a secret there; rather, it’s a daily source of continued danger, pain, and heartbreak.

The Foreigner Report (written by a foreigner): Laos Edition

The novelty bubble of interacting with English-speaking foreigners had been popped by the time we arrived in Luang Prabang, Laos. The entire small city is a UN World Heritage site. No buildings can be destroyed, renovated, or updated without the UN office’s permission, freezing the city in the French colonial era and inspiring flocks of tourists looking for a more “authentic” Southeast Asia experience.

We were among them and came face-to-face with our fellow backpackers in the quintessential backpacker hostel: The Mad Monkey.

When you check into The Mad Monkey, they gave you a bracelet with a microchip that serves as a room key, a method of charging food and drinks from the bar to your pre-loaded Mad Monkey account, and a branding. It’s waterproof; you never need to take it off during your stay.

Luang Prabang is not a party destination, but that doesn’t stop The Mad Monkey. Every night the bar is full of young-ish European and European-adjacent people playing drinking games, singing karaoke, and exchanging travel stories.

One British kid with the British haircut told me that I should set aside everything we had planned in Ho Chi Minh, switch flights to north Vietnam, and do The Loop on motorcycle. “It was the most life-changing experience I’ve ever had,” he said. “Seriously, I would drop everything and do it if I were you.” Those around the table nodded in agreement and compared the motorcycle models they used.

Everyone is friendly but have no misconceptions about the reality of hostel friendships. No one is looking for anything more than a friend for the night, travel companion for the next couple days, or bowling partner.

Yes, you read that right: bowling. The one place that is open past 10 pm in Luang Prabang is the bowling alley. So, every night at 10 pm when the bar closes, young people steadily trickle into rickshaws that have been waiting for them all evening, ready on demand to make the Mad Monkey-bowling alley drive as they did the night before and as they will do the next night.

We didn’t go bowling— not because we were sticking our noses up, adopting a holier-than-thou attitude to our fellow backpackers, but because we were exhausted each night. At 10 pm when the migration began, we always considered a night of bowling glory and low-stakes acquaintance. But we could never quite pull the trigger.

The boy who came in, threw up all over the shared bathroom, and then stumbled out to the rickshaws only confirmed our decision.

Vietnam

I arrived in Vietnam alone. I had accidentally bought the last ticket on the early flight just seconds before Lena. She was coming in on the late-night flight, and I had time to myself. I took a long bus ride into the city. Dark clouds formed on the horizon. We were arriving just at the beginning of the rainy season.

I had texted a PiA fellow living there about meeting up in “Ho Chi Minh City.” She told me everyone still calls it Saigon.

Unlike Bangkok, which seemed to balance its two halves — the inward and the outward facing — in some sort of harmony or compromise, Saigon felt more chaotic, edgier, more (in)tense.

Though this is obviously a blog and thus not even an attempt at any sort of “objective” analysis of anything, writing about Saigon is causing some sort of cognitive dissonance where I don’t know if I— or maybe any American— could ever see the city with objective eyes even if I wanted to.

I have watched Full Metal Jacket, Apocalypse Now, Deer Hunter, Good Morning Vietnam, and Platoon. I have read The Things They Carried, The Quiet American, and was reading The Sympathizer, a superbly well-written novel about the experience of a Communist double agent fleeing Saigon and escaping to America. So as I ate pho, witnessed the nimble dance of the endless motorbikes weaving past, along side, and through each other, and watched lighting crackle as day turned to dusk, I felt tension— or I superimposed tension on this place.

Indeed, thinking back, there were many things that countered my possibly artificially-created tension in the city. In the public parks, Vietnamese teens set up mobile badminton nets and played King of the Court. The park was nearly silent besides the soft whistle of the birdie flying through the air and quiet giggles after swings and misses.

I wonder too if part of the tension I felt in Saigon was not artificially imposed by myself but a deliberate campaign by the city’s denizens. One only needs to walk down Đ. Bùi Viện (pictured below) to see how Vietnamese free market entrepreneurs in this supposedly Communist country try to make a buck by selling some of the Western-created narrative that Vietnam is wild, exotic, and a bit dangerous back to Western tourists. Perhaps it is only just. Perhaps it is the exploited becoming the exploiters to, once again, please the original exploiters. Maybe that’s an improvement? I don’t know.

The Foreigner Report (written by a foreigner): Vietnam Edition

He sat on the one couch in the cramped hostel lobby. Behind him, the reception desk overflowed with papers. In front of him, a half-eaten pizza, a cake missing three pieces, and a large bottle of coke sat on a low table. To his left, two exotic cats that looked like mini leopards lazed about. Their leashes kept them from wandering out onto the streets.

We stopped and said happy birthday. He was American, and we started going through the usuals: What state? Which city? How long have you been abroad? When we asked him how old he was turning, he said he’d only tell us if we guessed first. He looked satisfied when I lowballed him by five years.

He was a 31-year-old guy from Seattle. He told us about how he recently quit his job in the US to pursue travel vlogging full time.

He had an easy, wide smile and the frame of an Olympic swimmer. It made sense that people might want watch him vlog through Phuket, Kuala Lumpur, and Bali.

He asked us if we had any crazy stories from our travels. I asked him to go first. He told us about a time he almost missed a bus to another bus in southern Thailand or something. The conversation never looped back.

Later that night, I scoured YouTube for his channel with the only biographical piece of information I knew about him: his name was Aaron.

I never found it.

Prediction #2 - Achieved

In the wet room bathroom in our hostel, I looked down and noticed raised red dots were all over my hands and forearms. They didn’t itch and weren’t particularly sensitive. But, they were there, and I thought hmm that’s not ideal.

Two days later, Lena and I arrived back in Bangkok, each of us covered from head-to-toe in this red rash. After a couple days of fatigue and dueling diagnoses (dermatitis vs. virus of an unknown origin) from different hospitals, we ate our last dinner in Southeast Asia. We hid our speckled skin under the table and ate at the restaurant where pad thai was first served.1

The next morning, we wore long sleeves and long pants to the airport for our flight back to Almaty. When we found the characteristically haphazard line in front of the Air Astana check-in counter, I looked around. Kazakh men with chin-strap beards wearing sleeveless shirts and Russian families sporting bad sunburns anxiously stood in line with us. Many passengers carried plastic containers with cut-outs exposing their precious cargo: mangos, dragon fruit, and all the other fruits that were hard to find and impossible to buy at a reasonable price in Kazakhstan. I joked about our misfortune of being placed in a country so isolated and infertile that people were hauling home fruit to last the summer.

Yet, the day after we got back, I looked in the mirror. The rash was gone.

There are no mangos in Kazakhstan. But it’s the origin of apples, I believe the mountain air somehow cured my mysterious illness, and that’s more than enough.

Prediction #3 - Mysterious rash is half credit.

Back Home

Three and a half hours into the Peak Furmanov hike, we ran into what must be a very common predicament for amateurs in over their head: the peak was in sight, but we had far underestimated the mountain.

We had heard Peak Furmanov was a “classic Almaty hike.” The signs at the start of the trail said it was easy. I suppose the first two-thirds of the hike were generally easy. But, the final push to the rocky peak made the easy classification laughable.

We climbed over boulders and walked through knee-deep snow. The mountain’s weather turned and within minutes, flurries of fresh snowflakes were hitting our faces, the seventy-degree day 2,500 meters below us only a memory.

The top of peak did not disappoint. On one side of us, the Tian Shan mountain range stretched out, the highest peaks clouded and covered in snow. On the other side, we saw the mountains turn into rolling hills then the sprawling city that I have called home for the last nine months.

Thanks for reading! Please let me know if you see any mistakes. And I do truly mean that— I’ve found a few after publishing and always feel embarrassed.

We’re really entering the home stretch now. This should be the penultimate blog post. I’m thinking about if and how I might continue to write in the future. We’ll see how things work out I guess. Fingers crossed. But for now, if you haven’t checked out the piece I wrote for The Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle, you can find it here or on the “notes” feature of this Substack.

With love,

Jack Styler

Despite the dueling diagnoses, we both were told we were not contagious by doctors.

![[video-to-gif output image] [video-to-gif output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!KG44!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff7bca715-e6b2-47c7-9807-1119d6ec404a_600x800.gif)

I’m waiting for more talks about ur experience at work w ur students, colleagues

Another thoughtful and reflective post. Thank you for sharing your journey.